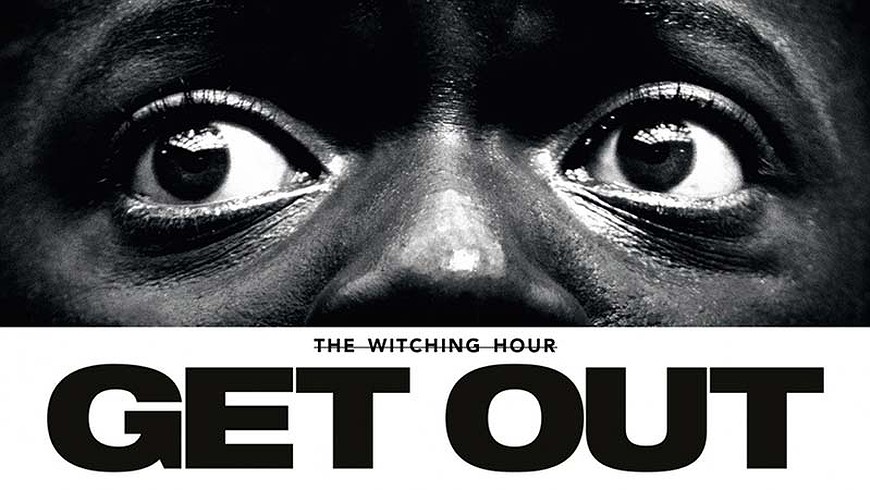

Get Out

Alara Drahşan

Films are divided into genres. There are semantic elements of each genre which are composed through time by their frequent usage in films. Each genre is divided in itself by its own differences and can be related to other genres by their common elements. Horror Genre

can be read under body genres because of the way the characters are dealt with and its effect on the body of the audience. Horror Genre puts the topic of body as its principal.

In this essay, I will be focusing on Get Out (2017) by Jordan Peele from the perspective of Horror Genre by supplementing it with the Gothic Genre view point as well. Furthermore, I will discuss how the film deals with the topic of race and whether it succeeds in becoming a horror film or not.

Get Out (2017) by Jordan Peele stated as a horror film is centered on a black guy, Chris, who visits the family of his white girlfriend, Rose, to be introduced to her family. The family describes themselves as “black culture friendly” and frequently highlights the race topic to Chris. They quickly get his attention through their lifestyle. Chris finds himself in a position where he questions the family members’ disturbing behaviours and suddenly becomes alienated by them.

“Race” topic is repeated throughout the film and it is what the film’s horror elements are fed from. Meaning; the elements that are giving the film its horror are composed of the white and black “body” differences. What is more, these “differences” are what the film turns its narrative direction to. Chris, being a black guy in a white family, starts realizing that he is not the only black person the family. In this article, first I would like to talk more about whether the film succeeds in its genre or not and the reasons for it. Secondly, I would like to focus on how it deals with the race topic.

It is important to state what makes a film a horror film. One of the most basic descriptions is that it scares the audience. It is indeed a hectic genre meaning it creates a reaction through the audiences’ body. Linda Williams states in Film Bodies: Gender, Genre, and Excess, “horror films create a world around the encounters that come “too early”.” Get Out shapes its story and the mise-en-scène around the semantic elements of the horror genre yet these elements are not enough to describe the film as a “horror film”. Horror genre itself has been one of the most engrossing genres. Yet, the reason why Get Out fails to succeed as a good horror film is “the expectation of horror”. If there is one horror in Get Out that is the horror Chris is living inside his mind.

The horror in the film is given through the feelings of the main character, which are mostly psychological and what the audience sees is its visual form. As I stated horror as a body genre, this is rarely a hectic film. In Get Out “coming too early” is more like, “there is something and I need to examine it more in order not to be caught off-guarded”. This is what sets suspicion. Suspicion breaks the effect of surprise which horror aims at. The one genre Get Out succeeds in is the Gothic Genre. In my opinion, the film is not a horror film but rather a Gothic film; more specifically, a male gothic.

One of the distinctive factors for that is the fact that, whether it is a female or a male gothic, “gothic films” are fed by paranoia. In female gothics, paranoia is seen when the female character starts thinking that she is going mad and doubts herself. Whereas in male gothic the paranoia comes from outside. The male character starts doubting the people around him and feels alienated from his surroundings.

Mainly, as I stated above, like the paranoia in the male gothic, the horror in Chris’s mind makes him doubt the people around him and see them as a threat. What is more, instead of saying “I am going mad”, he quickly makes up his mind that the family and the people working for them are playing a game on him. That’s why, the horror does not pass to the audience. Chris is living the horror in his mind and the audience sees this horror indirectly. It creates rather suspense, a journey of doubt throughout the film instead of unexpected events leaving the audience in horror.

Yet because these two genres have similar characteristics, Get Out can be read as horror for some parts. Mainly, it is because both genres are fed from “fear and violence”. For example, “the fantasy of castration”, as a part of a horror (and also gothic film), is literally a display of what Chris goes throughout the film. He is victimized by the female character because of his physical appearance. The reason Rose is with him (sexuality) is because he is black (physical appearance). “Horror is the genre that seems to endlessly repeat the trauma of castration as if to “explain”, by repetitious mastery, the originary problem of sexual difference.” (Williams, Film Bodies: Gender, Genre, and Excess, p.10) As it is stated, in Get Out “the repetition” is what gets Chris into the house and stopping the castration is what gets him out of it.

Secondly, Black and White differences have been highlighted frequently throughout the film. Today when violence against black people still continues, “the way” to equalize differences has “tendencies” to display the differences more. Get Out is one of the best examples for showing the differences and opening up the race topic by creating a “tolerated” world to the black culture. The language shows this racism “tacitly”, which maybe more subliminal and potentially more dangerous. The film showcases the prejudice towards a black person from the start by thinking he owns the black culture and the bias that comes with it.

All in all, there are a lot of concerns to discuss in Get Out. Yet, horror and race are really dominant in the film. The genre creates suspense in narration, which serves the function of the story itself. The colour differences say more about the hidden view of people towards colour in a subtle way. It states racism can also be shown quietly, non-violently yet it does not make it less racist.

Notes

Williams, L. (1991). Film Bodies: Gender, Genre, and Excess. Film Quarterly, 44(4), 2-13.

previous

article

next

article Twitter Google Plus Facebook